Muddy Roads Through Dumfries

David Cuff, May 2024

Photo by John Kenna Hillers. Colorization by Brad Zang

Photo by John Kenna Hillers. Colorization by Brad ZangThis author’s favorite picture taken in Prince William County is of a car driving south on the then Washington-Richmond Road, today Route 1 in Dumfries within eyesight of the still standing William’s Ordinary, which at the time, "Ordinary" was a common word describing a hotel and restaurant within one building. The car has four well dressed gentlemen riding in the two plus two seating configuration. This image has things I like but lacked specifics, until recently. The photos are perfectly taken, clear and in focus, have great focal point, contain a great looking car of unknown manufacture, the best photo has a still standing 1790ish structure in the background, and shows what roads were like in the wet season in Prince William County.

The car is magnificent with its presumed shiny black paint and unusual for the time, flat fenders and single front bumper bar. The bottom of the windshield has a slight curve to it, following the curve of the hood, the headlights appear to have ornate glass lenses that give the illusion of crystals in the headlights, surely billed as a light dispersing amenity to spread the light out and provide better visibility in the extreme nighttime darkness with little to no light in many areas. The fenders are flat, which is unusual for the era of curved fenders that flow over rounded tires. These fenders are almost utilitarian in design, with the lack of curves, the steel they are produced from must be thicker than the standard curved fender seen on nearly every other car of the time since the curvature of fenders adds rigidity. While the fender is flat, the front and rear edges have a subtle radius on them, most back portions of fenders of this era are flat or 90 degrees from the long plane of the fender. The window is a standard split window to allow air flow to the occupants. The frame of the window doesn’t appear to attach on the outer areas as other cars of this era do, the bottom of the frame curves without attaching to the body of the car with a bulky bracket. The retractable top provides protection from rain and came with installable side curtains to fully enclose the car but fully enclosed metal bodied cars weren’t popular or affordable by the public for a few more years.

Cropped - Photo by John Kenna Hillers

Cropped - Photo by John Kenna HillersUntil recently the make and model of the car was unknown. Its design features mentioned above quickly excluded the well known car makers of this era such as Ford, Chevrolet, Chrysler, and even high end makers like Pierce-Arrow. A few cars that share some design details with the pictured car include the short lived Pan Automobile of St. Cloud, Minnesota, the Dodge Brothers touring car, and the 1917 Chevrolet Series D V-8 touring automobile.

After consultation with Bob Lipnichan, owner of a Standard Eight automobile and who runs the “Butlers Standard Eight” facebook page dedicated to Standard Eight automobiles, the car in the picture appears to be a 1919 five passenger touring model made by the Standard Steel Car Company in their Butler, Pennsylvania plant that stretched more than a half-mile.

Cropped - Photo by John Kenna Hillers

Cropped - Photo by John Kenna HillersThe company started in 1902 with financial backing from Andrew Mellon with the goal of making railcars for industry but quickly began making passenger railcars. Output of railcars peaked in 1907 with 29,411 being produced. The company acquired several other railcar manufacturers from Massachusetts to Richmond Virginia along the east coast and one from Ohio and Indiana. Following the death of the two men instrumental in founding the company, it was sold to Pullman Inc. in 1929. In 1934, the companies merged to form the Pullman-Standard Company.

The Standard Steel Car Company produced passenger automobiles between 1915 and 1921. The average price of a model was about $3,000 in 1920, more than $48,000 in 2024 money. Standard's best year was 1917 when about 2,300 cars were built. The Post-World War I recession and Depression of 1920-21 hurt the Standard Steel Car Company and led to its demise in early 1921. Following the closure of the automobile plant the factory was sold to the American Austin Company where they produced their cartoon looking cars.

The large brick building in the back of the main picture still stands today. It was constructed about 1790, nine years before the death of George Washington, who is known to have visited Dumfries often while traveling. The structure features a header bond brick pattern which means the standard red clay bricks are laid with the short end facing out. This was to show wealth, since this method used more bricks and took more labor to install. The structure has seen many uses in its lifetime from an ordinary, hotel, merchant store, and private residence. Today, it's owned by the Prince William County Government and is used as the office for the Preservation Division which manages the historic properties owned by the county government and shared with the public.

Cropped - Photo by John Kenna Hillers

Cropped - Photo by John Kenna HillersThe photographs were taken by John Kenna Hillers Jr. (1888-1945). His photographs were often stamped the same as his father’s, “J. K. Hillers”. Although not a true junior as his famous father's middle name was Karl, not Kenna. It appears that both Hillers went by “Jack”. At the time, Junior was working for the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads under the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The group of well dressed gentlemen were out on an auto tour that traveled south from Maryland to Dumfries and likely beyond. This trip was a little over a year after the Concrete Road was constructed on Quantico Marine Corps Base that was documented by the Bureau of Public Roads and published in the July 1918 issue of the Public Roads journal.

From the May-June issue of Virginia Road Builder journal we know the improvement time frame of this section of Route 1. Its first major improvement was built 18' wide of concrete that was 6” thick on the edges and 8” thick in the middle in 1923. The road was widened in 1933 to 30' with reinforced concrete, and widened to 40' in 1938 with reinforced concrete. Since 1938 the State has applied an asphalt surface, the majority of which was applied in 1941. In the 1937 image taken by Hillers from nearly the same location as the 1919 image it appears the road is asphalt, known in the industry at the time as bituminous concrete.

Hillers Jr. followed his father’s career path of photography. He married Lela Elizabeth Eliason Hillers in 1912 and had two sons, a true junior, John Kenna Hillers in 1916 and Richard Charles Hillers in 1922. The photographer died in 1945 at the age of 57. He was laid to rest in Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, D.C. His wife lived until 1974, at the age of 84 and was laid to rest next to her long deceased husband.

The photographer’s father, John Karl Hillers was a prominent photographer known for his work in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly in the American West. He was born in Hanover, Germany, in 1843 and immigrated to the United States in 1852. John Karl lived to be 81 years old until his death in 1925 and was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery.

John Karl's photography career began when he joined John Wesley Powell's second expedition to the American West in 1871. Powell was a geologist and explorer who led expeditions to map and study the western United States, particularly the Colorado River and the Grand Canyon. John Karl served as the expedition's photographer, capturing images of the landscapes, Native American tribes, and geological formations they encountered.

John Karl's photographs from the Powell expeditions are highly regarded for their technical quality and artistic composition. He used large-format cameras and the wet-plate collodion process, which required meticulous preparation and skill. Despite the challenges of working in remote and rugged terrain, Hillers produced stunning images that documented the natural beauty and cultural richness of the American West.

After his time with Powell, John Karl continued to work as a photographer for the U.S. Geological Survey and the Bureau of American Ethnology. He photographed Native American communities, archaeological sites, and geological features across the West, contributing significantly to the visual record of this region during a period of rapid change and exploration.

John Karl's photographs are now held in various collections, including the Smithsonian Institution, the Library of Congress, and other museums and archives. His work continues to be studied and appreciated for its historical, cultural, and artistic significance, offering valuable insights into the landscapes and peoples of the American West during the late 19th century.

John Karl took amazing photographs within the United States but John Kenna took amazing photographs within Prince William County. John Kenna’s assignments took him throughout the United States as well as far away places like the Philippines. He took several photographs of roadways around the Washington D.C. area and documented the making of Travelers’ Toll, a movie produced by the Bureau of Public Roads that was released in 1929. Before his death he was also in the midwest photographing native americans, just as his father did.

Photos taken by John Kenna Hillers

Photos taken by John Kenna Hillers. Original description lines are below the photo. Note on the first and best image Hillers wasn't attributed as the photographer but based on the other images we assume he was.

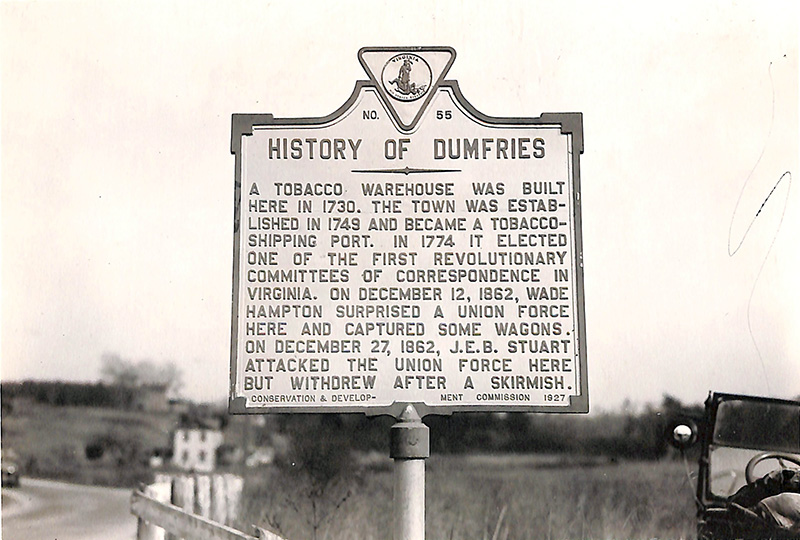

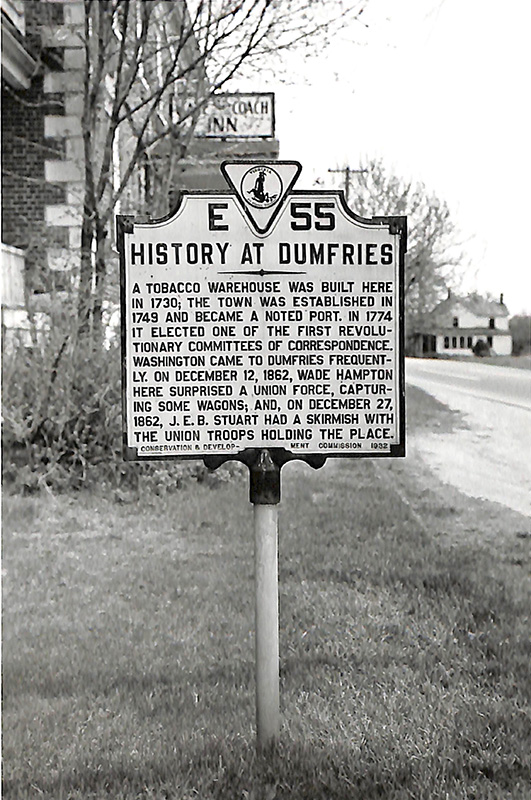

Historical Markers in Dumfries

There is no description for this image but this historical marker can be seen next to William's Ordinary in J. K. Hillers 1937 image.

There is no description for this image but this historical marker can be seen next to William's Ordinary in J. K. Hillers 1937 image.full size

Other Local Photos

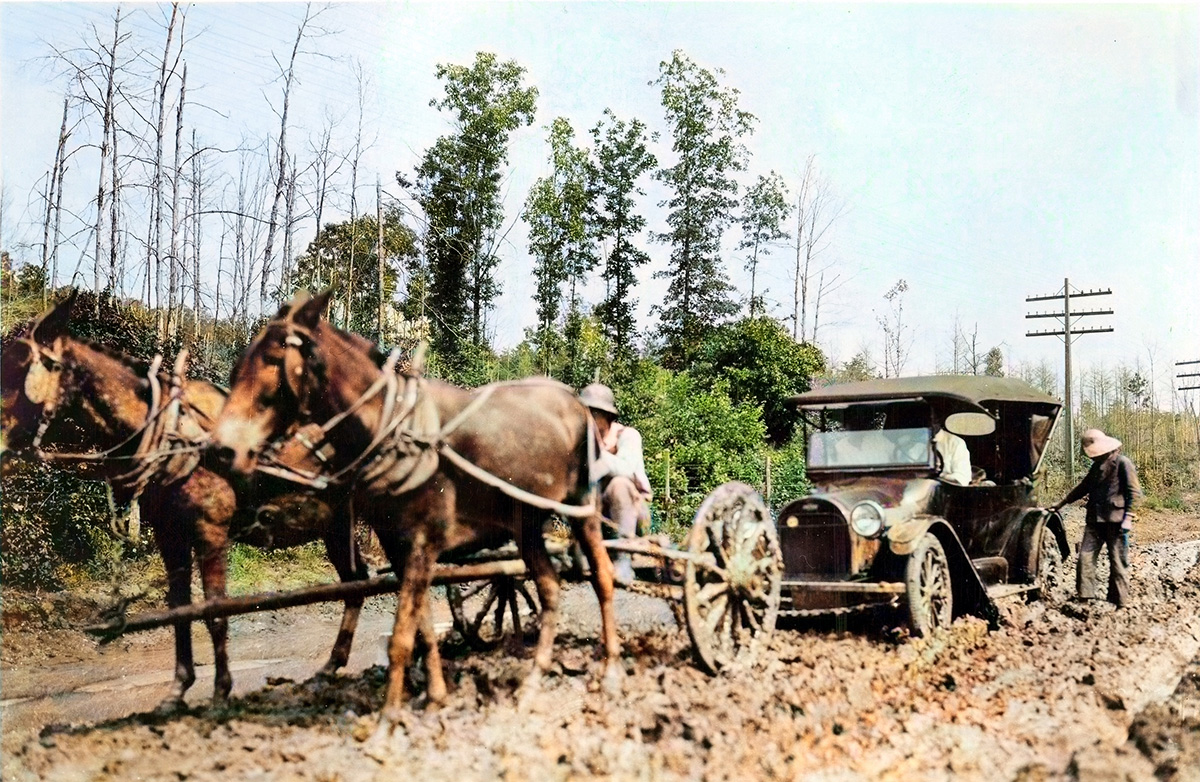

Two years before Hillers was in Dumfries photographing mud on official business, M.O. Eldridge was also in the area photographing locals stuck in the mud. Eldridge was researched but no information on the photographer was found.

Automobile being dragged out of the Road by mules near Dumfries, Virginia. Taken by M. O. Eldridge. July 1917.

Automobile being dragged out of the Road by mules near Dumfries, Virginia. Taken by M. O. Eldridge. July 1917.full size

Road on Chapawamsick Creek near Dumfries. Taken by M. O. Eldridge. July 1917. Colorized by Brad Zang.

Road on Chapawamsick Creek near Dumfries. Taken by M. O. Eldridge. July 1917. Colorized by Brad Zang.full size

Road on Chapawamsick Creek near Dumfries. Taken by M. O. Eldridge. July 1917. Colorized by Brad Zang.

Road on Chapawamsick Creek near Dumfries. Taken by M. O. Eldridge. July 1917. Colorized by Brad Zang.full size

Automobile being dragged out of the Road by mules near Dumfries, Virginia. Taken by M. O. Eldridge. July 1917. Colorized by Brad Zang.

Automobile being dragged out of the Road by mules near Dumfries, Virginia. Taken by M. O. Eldridge. July 1917. Colorized by Brad Zang.full size