Long Line of Cemetery Caretakers

By David Cuff, Sept. 2016

It’s the first day of July and 47-year-old Susan R. Morton pushes her way through 50 feet of underbrush to the once active White Hall Church and cemetery near Nokesville, south of the sharp turn in front of the Smith farm on Aden Road. The married mother of five has come to record the condition of the cemetery that predates the church which has been abandoned since 1910. Morton is head of the Work Projects Administration Writers’ Program of Prince William County. The year is 1937 and the Nokesville area is scattered with small farms where the families are trying to survive just a few years after the great depression.

Most of the over 420 cemeteries in Prince William County belong to family members who worked the small farms that once dominated the county. In the case of the first Harrison to settle in Virginia and the first white man to step foot in Loudoun County, Burr Harrison, whose death occurred in 1706, has been resting in peace along the Chopawamsic Creek for 310 years.

In recent years with the last available land in the Dale City area being developed into housing developments these once hidden and forgotten cemeteries are being brought into plain view with new homes being built just feet away. Local history buffs have known about the cemeteries but the average new resident jogging down running trails or sidewalks hasn’t realized there are cemeteries scattered about, until the developer comes in and builds houses nearby. The developer usually installs a fence around the cemetery and 83-year-old Bill Olson, the most dedicated cemetery protector in the county places a small brass nameplate with the name of the cemetery.

Prince William County has a long history of dedicated residents who have an interest in identifying, locating, and restoring area cemeteries.

Susan R. Morton was the first whose work was published and is still found on the internet today. She lived in the Haymarket area for about a decade in the 1930s. She wasn’t only interested in the area cemeteries. She was a passionate speaker who gave talks on various houses in the area and would talk to school children about the Doeg Indians.

Four decades after Morton, third generation county resident E.R. Conner III would visit the same cemetery as Morton did, only to find it in worse condition. Noted in Conner’s notes are that cattle have been trampling the grave markers in the cemetery. During Washington D.C.’s economic boom and rapid population growth, the demand for milk would be supplied largely by Prince William County farmers, many of them from the Nokesville area. Conner visited over 100 hundred cemeteries in the county and in 1981 published a book titled “100 Old Cemeteries of Prince William County Virginia”. The book includes surveys of the cemeteries, drawings of the location in some cases, grave layout, and information supplied by long time area residence which might be considered the most valuable information.

In the late 1990s the Prince William County Historical Commission wanted to locate all of the cemeteries in the county. During this time the development in the county was escalating in a rapid pace and the destruction and development of old family farms were numerous.

The Prince William Historical Commission and the County Planning Office decided to fund a project to locate and map the county cemeteries. They enlisted former commission member Ron Turner to head the project. The project located over 400 cemeteries within Prince William County.

The first thing Turner did was contact Howard Thompson, a retired teacher who was widely known as the expert on the subject. Howard knew, by memory the location of more than 100 cemeteries that were located while volunteering at the Manassas Battlefield, Prince William Forest Park, and Beverly Mill. Turner said “Howard was a tireless worker that deserves most of the credit for this project.”

While the original task was only to locate the cemeteries and take GPS coordinates of the location, Tuner documented other important information such as number of graves, the types of markers, information on the graves, and the general condition of the cemetery.

Ads were put in the local newspapers requesting information on local cemeteries, letters or calls would come in and Turner would contact the person to arrange a field visit. During this time Turner would learn valuable information only known to family members or local residents.

Turner’s 1991 visit found White Hall Cemetery to be in the same condition as Morton did, 54 years after her visit. During the summer months the undergrowth in the wooded area was so thick grave markers weren’t visible from Aden Road. With nearly 100 graves, this cemetery is relatively large compared to most of the other cemeteries in the county.

In 2013 Robert Moser was looking for a new cemetery project to start after finishing the lengthy cleanup of Greenwood Presbyterian Church Cemetery on Delaney Road in Dale City. Moser’s first visit to White Hall Cemetery was in the summer months when the growth was in full force. Moser had to park in Virginia Kidd’s driveway and climb the fence between the cemetery property and her longtime home to gain access to the cemetery as no driveway over the ditch along Aden Road existed.

Progress was slow and steady as the married father only had a few hours on Sunday mornings to work on the project. Brush was cleared, the ground was probed for lost stones and several were found, information was taken in the type of stone, location, and any inscription was recorded. Once the underbrush was cleared the task of resetting the stones was started. Years of neglect, cows trampling the stones, and assumed vandalism took its toll on the grave markers in the cemetery. The broken markers were spliced back together with wooden boards and long bolts assembled by Bill Olson. Some markers were essentially glued back together with epoxy developed for this very task. Some of the markers just needed to be reset, once the proper location was determined a hole was dug and the marker was placed. A section of the cemetery has a row of children, nearly all of their markers needed to be reset or repaired.

In 2015 Eagle Scout Jamey Bococompani raised money, purchased, and installed 230 feet of split rail fence and built four wooden benches placed at the cemetery. Bill Olson worked with VDOT to get a pipe placed in the ditch and Bill shoveled the majority of the bank to cover the pipe.

Monthly maintenance takes place at White Hall Cemetery as needed. A few weeks ago Robert Moser and Bill Olson spent a few hours cutting the tall grass around the old church foundation. Olson has the energy and dedication like no other. He spends countless hours on cemeteries in Prince William County.

Future plans for White Hall Cemetery include placement of a roadside historical marker and a low rise wooden wall over the church foundation. The wall is being built with reclaimed wood donated by a local developer.

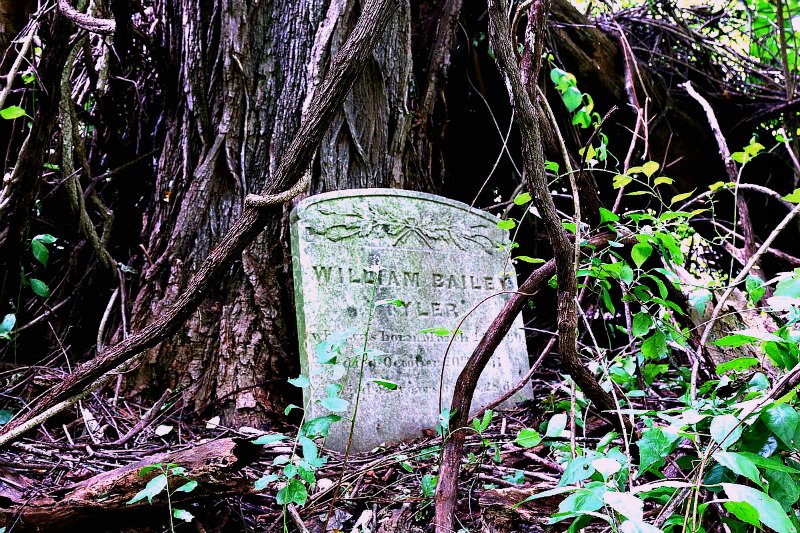

Robert Moser has started a new project. When visiting the site for the first time a few weeks ago he was excited to find misplaced markers under trees or under a thick layer of underbrush. He couldn’t wait to start the initial cleanup of the entry area so he could bring in the needed equipment. With only approximately 12 graves, this cemetery is average size compared to others in the county. Headstones are displaced from their nonnative locations but some of the graves have small footstones with initials carved in them so the opportunity to marry the headstone with the proper grave is probable.

This cemetery was once part of the 1,115 acre estate Martin Cockburn purchased in 1789. Cockburn’s primary residence was near Mount Vernon and Gunston Hall in Fairfax County. He was friends with George Mason and executor of his will. In 1790 Cockburn constructed a summer home on the property and named it “The Shelter”. Generations later the property fell to the ownership of the Tyler family which it remained for decades. Standing vacant since the 1940s, by the 1980s the estate was reduced to just 128 acres and the house was in ruins. In 1997 the property was developed into large stately homes Cockburn couldn’t help not to admire.

Morton visited this cemetery in March of 1938. In her notes she transcribed the grave markers, which was very important since at this time the nearby farm known as “Clifton” had a tenant and this cemetery was just a few feet east of the main road that split the fields and led to the farmhouse so it’s assumed the cemetery was in decent condition at the time.

Cattle grazed in the area during the 1970s had damaged or toppled markers with familiar county names such as Tyler, Harrison, and Chinn.

Conner also visited in August of 1979 and noted the still present undergrowth. Conner didn’t mention the condition but he included sketches in his book that note the grave layout and the location of the cemetery in relation to “Clifton” and The Shelter”, which at the time, were both abandoned.

Turner noted the cemetery was “completely overgrown” in the report following his visit to the cemetery in 1997.

In the next few months Moser, Olson, and others will be working on clearing the underbrush, uncovering grave markers, probing the ground for lost markers, and relocating the markers to their proper location. The work is slow but personally rewarding.

Access to this cemetery crosses personal property so the cemetery isn’t open to the public at this time.

A version of this story was published by InsideNOVA on Sept. 8th, 2016. The online version can be viewed at Prince William County keeps track of fading memories